производи Категорија

- ФМ предавател

- 0-50w 50w-1000w 2kw-10kw 10kw +

- ТВ предавател

- 0-50w 50-1kw 2kw-10kw

- FM антена

- ТВ Антена

- антена галантерија

- кабел конектор моќ сплитер Лажна транспорт

- RF транзистори

- Напојување

- Аудио опрема

- DTV преден крај опрема

- линк систем

- STL систем систем микробранова врска

- FM радио

- мерач на моќност

- други производи

- Специјални за Коронавирус

производи Тагови

FMUSER сајтови

- es.fmuser.net

- it.fmuser.net

- fr.fmuser.net

- de.fmuser.net

- af.fmuser.net -> африканс

- sq.fmuser.net -> албански

- ar.fmuser.net -> арапски

- hy.fmuser.net -> ерменски

- az.fmuser.net -> азербејџански

- eu.fmuser.net -> баскиски

- be.fmuser.net -> белоруски

- bg.fmuser.net -> бугарски

- ca.fmuser.net -> каталонски

- zh-CN.fmuser.net -> кинески (поедноставен)

- zh-TW.fmuser.net -> кинески (традиционален)

- hr.fmuser.net -> хрватски

- cs.fmuser.net -> чешки

- da.fmuser.net -> дански

- nl.fmuser.net -> холандски

- et.fmuser.net -> естонски

- tl.fmuser.net -> филипински

- fi.fmuser.net -> фински

- fr.fmuser.net -> француски

- gl.fmuser.net -> галициски

- ka.fmuser.net -> грузиски

- de.fmuser.net -> германски

- el.fmuser.net -> грчки

- ht.fmuser.net -> хаитски креолски

- iw.fmuser.net -> хебрејски

- hi.fmuser.net -> хинди

- hu.fmuser.net -> унгарски

- is.fmuser.net -> исландски

- id.fmuser.net -> индонезиски

- ga.fmuser.net -> ирски

- it.fmuser.net -> италијански

- ja.fmuser.net -> јапонски

- ko.fmuser.net -> корејски

- lv.fmuser.net -> латвиски

- lt.fmuser.net -> литвански

- mk.fmuser.net -> македонски

- ms.fmuser.net -> малајски

- mt.fmuser.net -> малтешки

- no.fmuser.net -> Норвешки

- fa.fmuser.net -> персиски

- pl.fmuser.net -> полски

- pt.fmuser.net -> Португалски

- ro.fmuser.net -> романски

- ru.fmuser.net -> руски

- sr.fmuser.net -> српски

- sk.fmuser.net -> словачки

- sl.fmuser.net -> словенечки

- es.fmuser.net -> шпански

- sw.fmuser.net -> свахили

- sv.fmuser.net -> шведски

- th.fmuser.net -> тајландски

- tr.fmuser.net -> турски

- uk.fmuser.net -> украински

- ur.fmuser.net -> урду

- vi.fmuser.net -> виетнамски

- cy.fmuser.net -> велшки

- yi.fmuser.net -> јидски

A Century of Live Sound

Date:2020/2/22 0:11:04 Hits:

How has the sound of live music changed over the decades? Join Sweetwater as we take a look at how new technologies have affected the way we experience — and perform — live music.

Unamplified performance

In the beginning, there was unamplified performance, and it was good. Audiences heard a natural blend of instruments and voices in an acoustic space. Regardless of the listener’s location in a multi-source environment, the sound was perceived as coming from the directions of the individual instruments, corresponding to what was seen. Musicians, confident that the sound they produced onstage was the sound that projected out to their audience, were in complete control of their sound and modified their playing according to what they wanted the audience to hear. Lastly, equipment considerations for live acoustic performances were modest. Musicians arrived at the gig with their instruments and, with no complex gear setups or sound “reinforcement,” could start playing within minutes.

The 20th century brought new recording and broadcast technologies, making it possible to reach larger populations with news and entertainment than ever before. The introduction of radio and the phonograph created giant markets for the proliferation of musical styles that accompanied the social upheaval of the new century. Jazz, in particular, spread from New Orleans to the rest of the country largely due to the reach of radio broadcasts and phonograph records. This all resulted in a growing number of music fans — and increased demand for live performances of the new music.

To meet that demand, music was performed for ever-larger audiences who came not only to listen — but also to dance and socialize. The era of the aristocratic class quietly listening to classical chamber music was eclipsed by the popular musical tastes of a growing middle class. Live performances of jazz, blues, country and western, swing, and big band music soon came to dominate the music scene, packing theaters and dance halls with fans. To be heard in these larger venues packed with people, unamplified music groups became larger, adding percussion, horn sections, and more. Guitars got larger bodies and steel strings. But ultimately, large musical groups were difficult to manage and expensive to book. Many small ensembles turned to electronic amplification as a way to entertain large audiences more economically.

Individual-instrument amplification

As the technology became available to amplify instruments such as guitar, individual-instrument (backline) amplification took off and went on to become the dominant method of amplifying acoustic performances for almost 50 years. By the mid-20th century, guitar, bass, piano, and vocals, among others, had all been successfully amplified, making it easy for smaller groups to achieve the volume levels required to fill a nightclub or dance hall. Indeed, for the first time in history, entirely new instruments — such as the solidbody electric bass and the Hawaiian guitar (lap steel), which only worked when amplified — were being invented. Amplification became the catalyst for the rapid evolution of musical styles. New genres such as rock ‘n’ roll were emerging, as a new generation of musicians took to the stage, tethered to their amps.

Amplification of individual instruments was essentially an extension of unamplified performance, with the benefits of such remaining largely intact. From the audience perspective, sound still emanated from where the eyes confirmed it should. But by the late 1950s, the post-war baby boom, economic growth, and advances in recording and broadcast technology meant that massive audiences had access to music like never before. Popular music acts were able to sell enough tickets to pack large venues that could accommodate thousands of fans. When the Beatles played to 56,000 screaming teenyboppers at Shea Stadium in 1965, the sound system proved incapable of delivering sufficient sound levels to most of the audience. The backline approach to amplification that had worked so well for so long was no longer satisfactory. Another approach to amplifying live music was needed.

In August 1969, four years after the Beatles played Shea, the Woodstock Festival was held on a dairy farm in Bethel, New York. The bespoke amplification system was designed by audio engineer Bill Hanley, who became known as “the father of festival sound.” Says Bill: “I built special speaker columns on the hills and had 16 loudspeaker arrays in a square platform going up to the hill on 70-foot towers. We set it up for 150,000 to 200,000 people. Of course, 500,000 showed up.” The actual attendance was closer to 400,000, but no matter — delivering clean, rock-level sound to the population of a small city spread over acres of farmland was no easy feat, especially considering the state of the art in pro audio gear at the time.

Triple-system amplification

The answer was a triple-system amplification approach consisting of backline (instrument) amps, stage monitors for the musicians to hear each other, and a public address (PA) system to serve the audience. The backline system was retained from the earlier individual-instrument approach, because these amps were by now considered the essence of certain instruments’ sounds — especially electric guitar. The monitor system, aimed away from the audience and toward the musicians, attempted to give individual musicians their own mix. The PA system projected sound into the audience, away from the stage.

Bill Hanley, designer of the Woodstock sound system, sitting at the mix position at Woodstock.

Hanley had to construct the PA system from scratch using available components. The half-ton “Woodstock Bins,” marine plywood cabinets fitted with multiple 15″ JBL drivers, delivered the low frequencies. Placed above, an array of multi-cell Altec horns carried the highs. Three transformers providing 2,000 amps of current powered the 10,000-watt amplification system: a hodgepodge of McIntosh MI-200 and MI-350 tube amps and the then-new solid-state Crown DC-300. On the mixing platform, about 75 feet from the stage, were stacks of simple Shure mixers and an LA-2A compressor; miles of cabling linked to the stage and out to the speaker towers.

By the 1970s, the triple-system approach had become the standard for large concert performances. Aspiring musicians naturally coveted the gear that successful artists used, and the pro audio equipment industry catered to this market segment by designing smaller, less-expensive triple-system amplification equipment. By the early 1980s, the triple system had become de rigueur for artists playing in venues of virtually any size — and it largely remains so today.

By the early ’70s, solid-state amplifiers had edged out tube gear in both the pro and consumer audio markets. Recording studio monitoring systems were now multi-amped by sophisticated behemoths such as the McIntosh MC-2300. At 300 watts per channel in stereo, or 600 watts bridged to mono, the 2300 was just the sort of reliable, high-wattage, high-fidelity amplifier live sound engineers needed for demanding professional applications such as arena concerts and outdoor music festivals, where failure was not an option.

In July 1973, three supergroups — the Grateful Dead, The Band, and the Allman Brothers — played to an audience of 600,000 at the Watkins Glen Summer Jam, held on an auto racetrack in upstate New York. Due to the crowd’s immense size, a significant number of concertgoers could neither see the stage, nor satisfactorily hear the music coming from it. Additional speaker towers were built, but this required more amplification. Sound engineer Janet Furman (yes, the same person who founded the Furman company that makes the power conditioners we all use) was dispatched by helicopter with six grand in cash to nearby Binghamton, home of McIntosh Laboratories, to purchase five more MC-2300 amplifiers. Although it was the weekend, Janet located the owner at his home, bought the amps off the factory floor, loaded them into the ’copter, and took off to fly back to the raceway.

With their primary focus on amplification power, missing from the sound crew’s calculations was weight. At 128 pounds, each MC-2300 was a substantial piece of gear. With the addition of 640 pounds of amplifiers to Janet and the pilot’s weight, the small helicopter struggled to maintain altitude, skirting high-rise buildings and narrowly averting calamity. But thanks to a combination of luck and persistence, they got back safely and the new amps were rigged into the sound system successfully. The enormous crowd got to enjoy high-quality sound and never knew the difference.

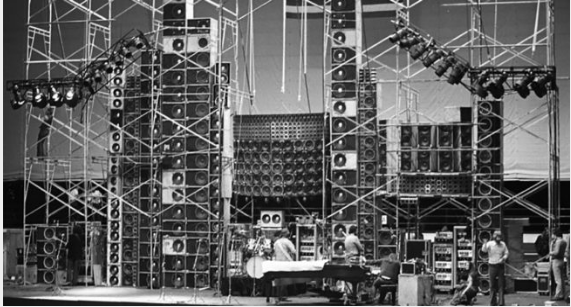

Live music had entered the age of brute force concert sound. It seemed there was no live sound problem you couldn’t solve by throwing more power at it. By December ’73, British prog-rock trio Emerson, Lake & Palmer’s stage setup had grown so massive and elaborate that the band’s Madison Square Garden shows — amplified by a custom 28,000-watt quadraphonic surround system — required five hours of load-in. Although only used for several months in 1974, the Dead’s infamous, mammoth Wall of Sound PA system (see image above) — renowned for its high fidelity, low distortion, and ability to project up to 600 feet without significant sonic degradation — was powered by 48 McIntosh MC-2300s.

Triple-system amplification isn’t perfect, however. Although coverage is generally acceptable, making these three systems work together to achieve sonic coherency remains a challenge. The sound from multiple speakers flooding a venue’s upper walls and ceiling can muddy the front-of-house mix with excessive reverberation. And source localization remains particularly problematic. An audience member hearing, say, a vocal coming from the nearest speaker column — which may be hundreds of feet away from the singer — can be disconcerting. And the powerful guitar amplifiers that proliferated in the late ’60s didn’t help. In addition to overwhelming the front-of-house mix for the audience near the stage, blaring instrument amps tend to make monitor mixes impossible to balance, instigating onstage volume wars (“more me”) among the musicians.

Excess volume is also an issue. Anyone who has attended a large concert (without wearing earplugs) in the last four decades has stood a good chance of coming home with ringing in their ears. So here’s a Sweetwater public service announcement: Whether you’re a music lover or a performing musician, repeated exposure to 120dB sound pressure levels will lead to permanent hearing damage. Full stop. Enter the quiet stage.

The state of the art

From digital wireless and in-ear monitoring to new PA system concepts, live sound technology has taken major strides forward in the last decade. One of the more interesting and beneficial developments has been the so-called “quiet stage.” In many bands — even ones that feature distorted rock guitar tones — you may be surprised to see the guitarist with a very small amp, or no amp at all. The guitar sounds like it’s being amplified by a huge Marshall stack but may well be coming from an amp modeler taken direct into the mixing board. Assuming an instrumental quartet where the bass and keyboards are taken direct, this means that the only acoustic sound being generated onstage is coming from the drums — and they may even be isolated with acrylic panels. The quiet stage gives the front-of-house engineer an opportunity to achieve a clean house mix without having to deal with muddy leakage from the stage. And with their in-ear monitors, musicians can clearly hear their individually tailored monitor mixes, putting them back in control of their music. Everyone’s happy.

Although today’s large concerts still utilize triple-system amplification, live sound applications for smaller venues have been the vanguard of new technologies. At Sweetwater, we see this in houses of worship, academic and corporate auditoriums, and smaller concert halls such as the recently renovated Clyde Theatre here in Fort Wayne — which features an all-new state-of-the-art sound system (powered by Sweetwater), incorporating the latest live sound technologies.

New public address concepts such as the Turbosound iNSPIRE, Bose L1, JBL EON One, and Fishman SA330x systems have tamed the problem of excessive reverberation, eliminated hot spots, and brought back the ability of the audience to localize sounds onstage — delivering clear, even sound to every seat in the house at reasonable volumes. And so, in effect, new technologies have brought us full circle, back to the simple joys of acoustic performance.

Остави порака

Список со пораки

Коментарите се објавуваат ...